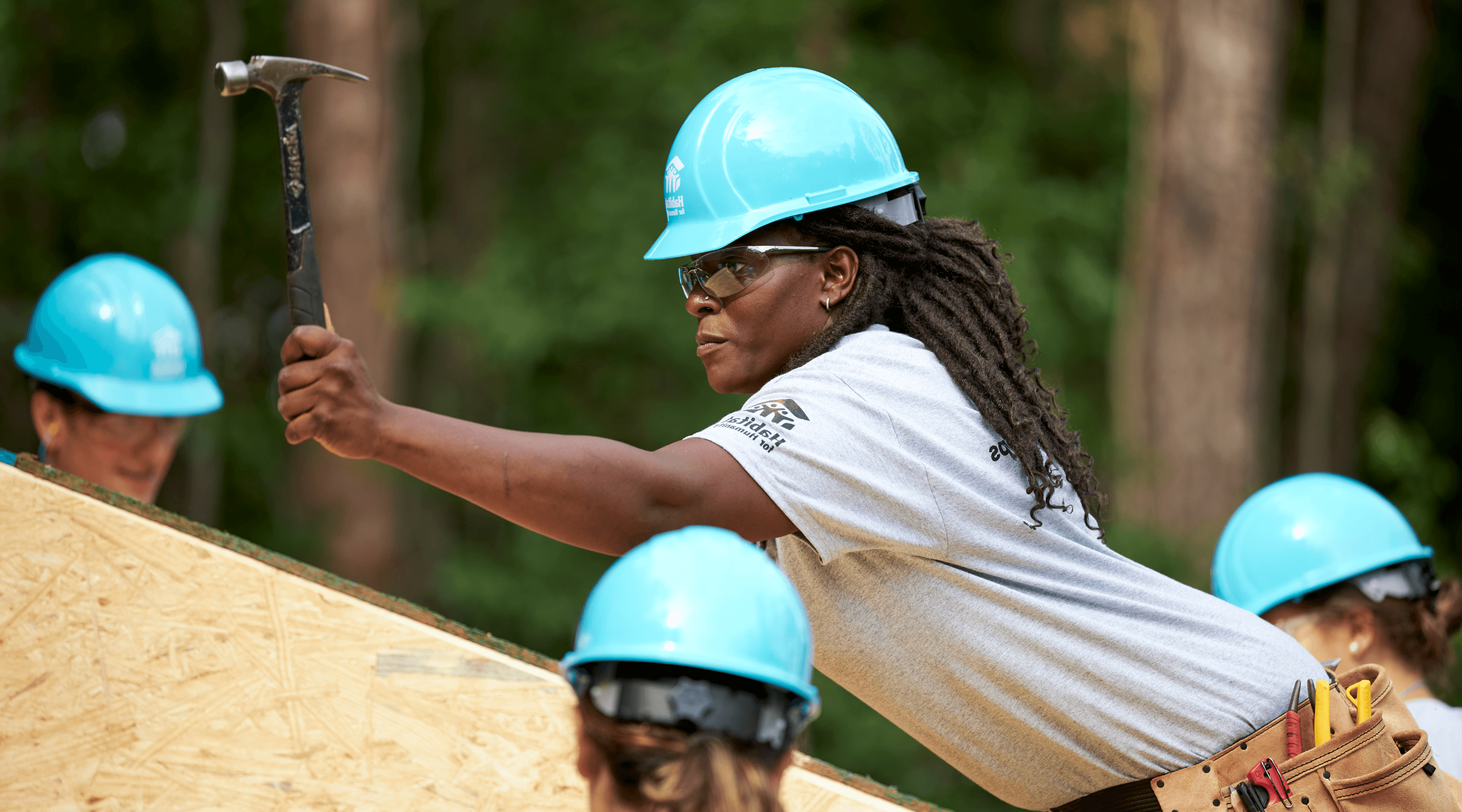

Make a Difference

Seeking to put God's love into action, Habitat for Humanity brings people together to build homes, communities and hope.

We build strength, stability and self-reliance through shelter.

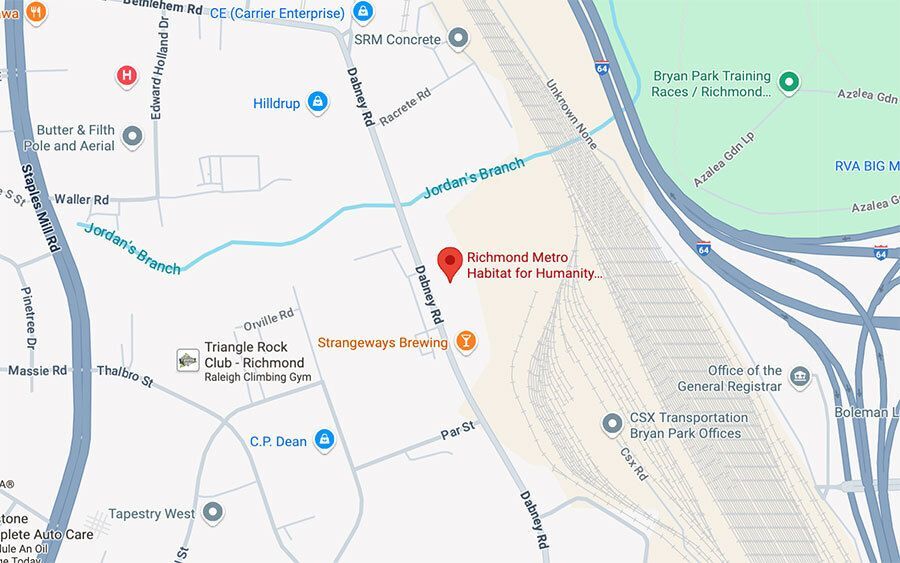

Richmond Metropolitan Habitat for Humanity partners with people in our community to build or improve the places they call home. Affordable housing plays a critical role in strong and stable communities.

-

Rose * Habitat homeowner

Rose * Habitat homeownerThis is my new beginning.

-

Affordable Homes Built

390+

-

2024 Volunteer Hours Served

34,038

-

Years Serving Richmond

39

With your support, Habitat homeowners achieve the strength, stability and independence they need to build a better life for themselves and for their families.