Buildings From the City of Richmond With Historical Significance

Putting the Spotlight on Black History in Richmond

Black History Month is an opportunity to understand Black history and to spotlight Black achievements. Carter G. Woodson, the inspiration behind Black History Month, famously wrote, “Knowing the past, opens the door to the future.” In honor of Black History Month, we will feature a few buildings from the City of Richmond that have historical significance.

Jackson Ward Cottage

(Photo credit: The JXN Project)

Abraham Skipwith, the first known free Black person to own a home in Jackson Ward, built his cottage in the mid-1790s after purchasing his freedom for the price of 40 pounds. Abraham Skipwith did something else unheard of for a Black man at the time. He executed a will and his home remained in the Skipwith-Roper family until 1905.

The cottage was extracted from its roots during the 1950s when white politicians and business leaders conspired to run what is now Interstate 95 through the heart of Jackson Ward. Mary Ross Scott Reed, who was among the founders of the Historic Richmond Foundation, along with her sister and cousin, stood in front of a bulldozer to prevent the cottage’s demolition. The cottage was moved to her family farm in Goochland County and today, her grandson, Scott Reed owns the cottage, which has been renovated and has an addition.

(Photo credit: Daniel Sangjib Min for Richmond Times-Dispatch)

Historic preservation is an important way for us to transmit our understanding of the past to future generations through restorative truth-telling and redemptive storytelling. Habitat for Humanity’s mission includes bringing people together to build communities and hope. This is done by giving homeowners the strength, stability, and independence they need to build a better life for themselves and for their families.

Dr. William Hughes House

(Photo credit: Richmond Times-Dispatch)

This 1915 Jackson Ward home was designed by Charles Thaddeus Russell, the first African American architect to be licensed in Richmond, for Dr. William Henry Hughes, a prominent African American physician. Later, it would become the Negro Training Center for the Blind, the only school for blind African Americans in Virginia.

In 2016, developer and preservationist, Zarina Fazaldin purchased the then boarded up and neglected property, and with the help of Virginia Housing, began to restore the structure. The building now serves as an affordable housing complex with four separate units.

(Photo credit: Richmond Magazine)

In response to the ever-growing need for shelter in Richmond and around the world, Habitat works in many ways: new construction, repairs to existing homes, small loans for incremental building and home improvements, help establishing title and ownership to land, advocacy for better laws and systems, disaster prevention and recovery, and more.

Maggie L. Walker High School

(Photo credit: Calder Loth, 2020 for the Virginia Department of Historic Resources)

The original building, Maggie L. Walker High School was first opened in the 1930s as a school for African Americans. It was one of two schools in the area for black students during the Jim Crow era.

It was named in honor of Maggie Lena Walker, the first woman and African American to operate a bank in the United States and was once attended by American civil rights lawyer and politician Henry L. Marsh, African American tennis pro Arthur Ashe, as well as pro football Hall-of-Famer Willie Lanier, and NBA great Bob Dandridge.

It reopened in fall 2001 after several million dollars of renovations and adopted the name Maggie L. Walker Governor’s School for Government and International Studies.

(Source: https://mlwgs.com/welcome-to-mlwgs/maggie-lena-walker/ )

Housing has a profound impact on education. Children raised in a Habitat home have a much more productive educational experience than those who move around frequently.

St. Luke Building

St. Luke Building is a historic office building in Richmond, Virginia. The building held the offices of the Independent Order of St. Luke, and the office of Maggie Lena Walker. It was built in 1902-1903.

The Independent Order of St. Luke’s mission was to foster African American economic independence. Maggie L. Walker was able to realize this goal as a leader and trailblazing African American businesswoman. Walker was the first African American woman to found a bank in U.S. history, and she leveraged her entrepreneurial success to advocate for African Americans’ civil rights.

Source: https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/historic-registers/127-0352/)

As the cost of housing rises in Richmond, families are forced to spend well over half their income on substandard housing, leaving little left over for other life necessities like gas, food, utilities, and healthcare. Habitat partner families report improved financial stability since moving and say that homeownership has positively impacted their ability to save money. Habitat makes sure housing stays affordable and allows families to save for the future.

First African Baptist Church

(Photo credit: Calder Loth, 2021 for the Virginia Department of Historic Resources)

The First African Baptist Church is a prominent Black church. Founded in 1841, its members initially included both slaves and freedmen. It has since had a major influence on the local black community and at one point, it was one of the largest Protestant churches in the United States.

In 1866, James H. Holmes, a former slave and highly gifted preacher, was elected assistant pastor, and in 1867 he became the pastor at the Church. Under Holmes, the church grew and became one of the largest churches in the country. In 1876 the original building was torn down and the congregation built a new church. The location of both the original church building and its replacement is at the corner of College Street and East Broad Street. The First African Baptist Church congregation moved in 1955. The church building was then sold to the Medical College of Virginia. The interior has been altered for use as classrooms and offices.

We must take time to reflect on the centuries of struggle for freedom and equality and to celebrate the contributions that African Americans have made to American history — both during this month and always. Equity lies at the heart of our mission. Decades of legalized discrimination in the housing industry has contributed to the racial disparity in housing that still exists today. We provide homeownership opportunities to families for whom it has not been traditionally possible.

Westhampton School

(Photo credit: Historic Richmond)

Westhampton School was an all-white school which denied entry to residents that lived right across the street. Former slaves founded Patterson, the surrounding community, in the 1870s. Richmond annexed the area but refused to provide basic services and tried to level the neighborhood in favor of a city park. Residents’ only source of water was a fire hydrant.

Habitat for Humanity strives to create diverse communities. Combating residential segregation fights systemic oppression and withholding of public services.

Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church

(Photo credit: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries. Photo taken by John Granderson Zehmer, 1942)

Founded in 1867 by former slave Reverend John Jasper, this is one of the oldest black churches in Richmond. It is located in Jackson Ward, once a vibrant black community referred to as the Harlem of the South. In the 1950s, the then all-white Virginia General Assembly created the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike authority, which routed the unpopular turnpike right through the center of Jackson Ward. It destroyed 1000 homes and eliminated pedestrian walkways between the new halves. The Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church’s secretary, Cerelia Johnson, operated an elevator in City Hall. She was able to overhear the conversations in City Hall and related the information to the community that worked to save the church. The church is the only building left north of Duval.

Urban planners historically slashed through black communities by building public projects using eminent domain and condemnation laws. Communities are nominally given opportunities to weigh-in, but corporate and stakeholder interests often hold more authority than the voices of residents. Habitat for Humanity is a vocal advocate for equitable planning and affordable housing.

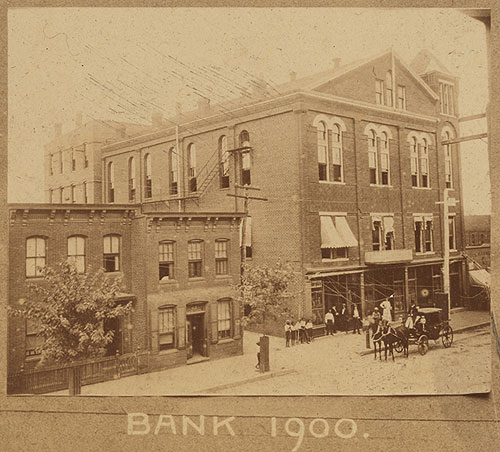

William Washington Browne House

This house in Jackson Ward was home to the first black-owned bank in the United States. It was founded by Reverend William Washington Browne, who escaped from slavery as a boy and fought for the Union Army. Later he joined the True Transformers, a temperance organization, that chartered the bank. He opened the bank in his home in 1889.

Generational wealth is key to racial equity. Jim Crow laws, oppressive urban planning (Jackson Ward), and the violence against black businesses centers (Tulsa) have made it difficult for black Americans to build wealth. Median net worth for white households is exponentially more than black households. Partnering with Habitat for Humanity enables families to get a jump start on wealth building through homeownership.

Community High School

(Photo credit: Don O’Keefe for Architecture Richmond)

In 1960, Gloria Jean Mead and Carol Irene Swann were the first black students to walk these steps into Chandler Junior High, now Community High School. True integration was a greater struggle and wasn’t fully achieved until a decade later. Now this school district is 90% people of color.

The northside of Richmond has seen many chapters. At various points it has been a streetcar neighborhood, a center of black intellectualism, a white flight neighborhood, and in the 1990s, an area known for poverty, violence, and abandoned buildings. Now the area faces rapid gentrification and skyrocketing property values.

While developers have profit as their bottom line, Habitat for Humanity’s bottom line is its mission: to build homes, communities, and hope. By providing more affordable housing in developing neighborhoods, the impact of gentrification is lessened.